What is the Big Bang Theory?

The Big Bang Theory explains how the universe began.

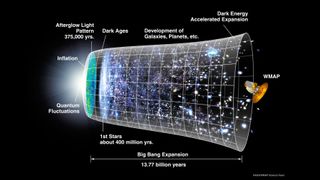

The Big Bang Theory is the leading explanation for how the universe began. Simply put, it says the universe as we know it started with an infinitely hot and dense single point that inflated and stretched — first at unimaginable speeds, and then at a more measurable rate — over the next 13.7 billion years to the still-expanding cosmos that we know today.

Existing technology doesn't yet allow astronomers to literally peer back at the universe's birth, much of what we understand about the Big Bang comes from mathematical formulas and models. Astronomers can, however, see the "echo" of the expansion through a phenomenon known as the cosmic microwave background.

While the majority of the astronomical community accepts the theory, there are some theorists who have alternative explanations besides the Big Bang — such as eternal inflation or an oscillating universe.

Related: What happened before the Big Bang?

The birth of the universe

Around 13.7 billion years ago, everything in the entire universe was condensed in an infinitesimally small singularity, a point of infinite denseness and heat.

Suddenly, an explosive expansion began, ballooning our universe outwards faster than the speed of light. This was a period of cosmic inflation that lasted mere fractions of a second — about 10^-32 of a second, according to physicist Alan Guth’s 1980 theory that changed the way we think about the Big Bang forever.

When cosmic inflation came to a sudden and still-mysterious end, the more classic descriptions of the Big Bang took hold. A flood of matter and radiation, known as "reheating," began populating our universe with the stuff we know today: particles, atoms, the stuff that would become stars and galaxies and so on.

This all happened within just the first second after the universe began, when the temperature of everything was still insanely hot, at about 10 billion degrees Fahrenheit (5.5 billion Celsius), according to NASA. The cosmos now contained a vast array of fundamental particles such as neutrons, electrons and protons — the raw materials that would become the building blocks for everything that exists today.

This early "soup" would have been impossible to actually see because it couldn't hold visible light. "The free electrons would have caused light (photons) to scatter the way sunlight scatters from the water droplets in clouds," NASA stated. Over time, however, these free electrons met up with nuclei and created neutral atoms or atoms with equal positive and negative electric charges.

This allowed light to finally shine through, about 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

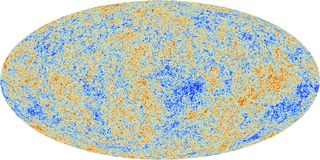

Sometimes called the "afterglow" of the Big Bang, this light is more properly known as the cosmic microwave background (CMB). It was first predicted by Ralph Alpher and other scientists in 1948 but was found only by accident almost 20 years later.

Related: Peering back to the Big Bang & early universe

This accidental discovery happened when Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, both of Bell Telephone Laboratories in New Jersey, were building a radio receiver in 1965 and picked up higher-than-expected temperatures, according to a NASA article. At first, they thought the anomaly was due to pigeons trying to roost inside the antenna and their waste, but they cleaned up the mess and killed the pigeons and the anomaly persisted.

Simultaneously, a Princeton University team led by Robert Dicke was trying to find evidence of the CMB and realized that Penzias and Wilson had stumbled upon it with their strange observations. The two groups each published papers in the Astrophysical Journal in 1965.

Big Bang theory FAQs answered by an expert

We asked Jason Steffens, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, a few frequently asked questions about the Big Bang Theory.

Jason Steffens is an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Has the Big Bang Theory been proven?

This isn't really a statement that we can make in general. The best we can do is say that there is strong evidence for the Big Bang Theory and that every test we throw at it comes back in support of the theory. Mathematicians prove things, but scientists can only say that the evidence supports a theory with some degree of confidence that is always less than 100%.

So, a short answer to a slightly different question is that all of the observational evidence that we've gathered is consistent with the predictions of the Big Bang Theory. The three most important observations are:

1) The Hubble Law shows that distant objects are receding from us at a rate proportional to their distance — which occurs when there is uniform expansion in all directions. This implies a history where everything was closer together.

2) The properties of the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB). This shows that the universe went through a transition from an ionized gas (a plasma) and a neutral gas. Such a transition implies a hot, dense early universe that cooled as it expanded. This transition happened after about 400,000 years following the Big Bang.

3) The relative abundances of light elements (He-4, He-3, Li-7, and Deuterium). These were formed during the era of Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN) in the first few minutes after the Big Bang. Their abundances show that the universe was really hot and really dense in the past (as opposed to the conditions when the CMB was formed, which was just regular hot and dense — there's about a factor of a million difference in temperature between when BBN occurred and when the CMB occurred).

Is there any occurrence that contradicts the Big Bang Theory?

Not that I know of. There are some issues that arise with the simplest model of the Big Bang, but those can be resolved by invoking a physical process that is still consistent with the basic premise of the Big Bang Theory. Specifically, the fact that the CMB temperature is the same everywhere, that the universe does not appear to have any curvature, and that density fluctuations from quantum mechanical predictions do not produce galaxy clusters of the right size and shape today. These three issues are resolved with the theory of inflation — which is part of the broader Big Bang Theory.

When was the Big Bang Theory established?

Who came up with the idea?

Hubble was really the person who set up the observations. Evidence continued to mount, especially in the 1970s with the detection of the CMB. The term "Big Bang" was first used in the late 1940s by the astronomer Fred Hoyle — eventually, it caught on in the 1970s.

Modelling the Big Bang

Because we can't see it directly, scientists have been trying to figure out how to "see" the Big Bang through other measures. In one case, cosmologists are pressing rewind to reach the first instant after the Big Bang by simulating 4,000 versions of the current universe on a massive supercomputer.

"We are trying to do something like guessing a baby photo of our universe from the latest picture," study leader Masato Shirasaki, a cosmologist at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), told our sister website Live Science.

With what is known about the universe today, the researchers in this 2021 study compared their understanding of how gravitational forces interacted in the primordial universe with their thousands of computer-modeled universes. If they could predict the starting conditions of their virtual universes, they hoped to be able to accurately predict what our own universe may have looked like back at the beginning.

Other researchers have chosen different paths to interrogate our universe's beginnings.

In a 2020 study, researchers did so by investigating the split between matter and antimatter. In the study, not yet peer-reviewed, they proposed that the imbalance in the amount of matter and antimatter in the universe is related to the universe's vast quantities of dark matter, an unknown substance that exerts influence over gravity and yet doesn't interact with light. They suggested that in the crucial moments immediately after the Big Bang, the universe may have been pushed to make more matter than its inverse, antimatter, which then could have led to the formation of dark matter.

The age of the universe

The CMB has been observed by many researchers now and with many spacecraft missions. One of the most famous space-faring missions to do so was NASA's Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite, which mapped the sky in the 1990s.

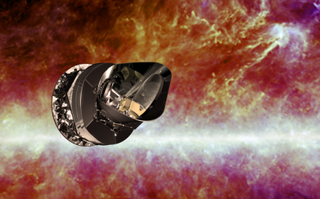

Several other missions have followed in COBE's footsteps, such as the BOOMERanG experiment (Balloon Observations of Millimetric Extragalactic Radiation and Geophysics), NASA's Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) and the European Space Agency's Planck satellite.

Planck's observations, first released in 2013, mapped the CMB in unprecedented detail and revealed that the universe was older than previously thought: 13.82 billion years old, rather than 13.7 billion years old. The research observatory's mission is ongoing and new maps of the CMB are released periodically.

Related: How old is the universe?

The maps give rise to new mysteries, however, such as why the Southern Hemisphere appears slightly redder (warmer) than the Northern Hemisphere. The Big Bang Theory says that the CMB would be mostly the same, no matter where you look.

Examining the CMB also gives astronomers clues as to the composition of the universe. Researchers think most of the cosmos is made up of matter and energy that cannot be "sensed" with our conventional instruments, leading to the names "dark matter" and "dark energy." It is thought that only 5% of the universe is made up of matter such as planets, stars and galaxies.

What are gravitational waves?

While astronomers study the universe's beginnings through creative measures and mathematical simulations, they've also sought proof of its rapid inflation. They have done this by observing gravitational waves, tiny perturbations in space-time that ripple outwards from great disturbances like, for instance, two colliding black holes or the universe's birth.

According to leading theories, in the first second after the universe was born, our cosmos ballooned faster than the speed of light. (That, by the way, does not violate Albert Einstein's speed limit. He once said that light speed is the fastest anything can travel within the universe — but that statement did not apply to the inflation of the universe itself.)

As the universe expanded, it created the CMB and a similar "background noise" made up of gravitational waves that, like the CMB, were a sort of static, detectable from all parts of the sky. Those gravitational waves, according to the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, produced a theorized barely-detectable polarization, one type of which is called "B-modes."

In 2014, astronomers said they had found evidence of B-modes using an Antarctic telescope called "Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization," or BICEP2.

"We're very confident that the signal that we're seeing is real, and it's on the sky," lead researcher John Kovac, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics told Space.com in March 2014.

But by June, the same team said that their findings could have been altered by galactic dust getting in the way of their field of view. That hypothesis was supported by new results from the Planck satellite.

By January 2015, researchers from both teams working together "confirmed that the Bicep signal was mostly, if not all, stardust," the New York Times said.

However, since then gravitational waves have not only been confirmed to exist, they have been observed multiple times.

These waves, which are not B-modes from the birth of the universe but rather from more recent collisions of black holes, have been detected multiple times by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), with the first-ever gravitational wave detection taking place in 2016.

A major gravitational wave breakthrough was announced on June 28, 2023 when teams of scientists around the world reported the discovery of a "low-pitch hum" of these cosmic ripples flowing through the Milky Way. While astronomers don't definitively know what's causing the hum, the detected signal is "compelling evidence" and consistent with theoretical expectations of gravitational waves emerging from copious pairs of "the most massive black holes in the entire universe" weighing as much as billions of suns, said Stephen Taylor, a gravitational wave astrophysicist at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee who co-led the research.

Read more: The gravitational wave background of the universe has been heard for the 1st time

Was the Big Bang an explosion?

Although the Big Bang is often described as an "explosion", that's a misleading image. In an explosion, fragments are flung out from a central point into a pre-existing space. If you were at the central point, you'd see all the fragments moving away from you at roughly the same speed.

But the Big Bang wasn't like that. It was an expansion of space itself – a concept that comes out of Einstein's equations of general relativity but has no counterpart in the classical physics of everyday life. It means that all the distances in the universe are stretching out at the same rate. Any two galaxies separated by distance X are receding from each other at the same speed, while a galaxy at distance 2X recedes at twice that speed.

The expansion of the universe

The universe is not only expanding, but expanding faster. This means that with time, nobody will be able to spot other galaxies from Earth or any other vantage point within our galaxy.

"We will see distant galaxies moving away from us, but their speed is increasing with time," Harvard University astronomer Avi Loeb said in a March 2014 Space.com article.

"So, if you wait long enough, eventually, a distant galaxy will reach the speed of light. What that means is that even light won't be able to bridge the gap that's being opened between that galaxy and us. There's no way for extraterrestrials on that galaxy to communicate with us, to send any signals that will reach us, once their galaxy is moving faster than light relative to us."

Related: 5 weird facts about seeing the universe's birth

Some physicists also suggest that the universe we experience is just one of many. In the "multiverse" model, different universes would coexist with each other like bubbles lying side by side. The theory suggests that in that first big push of inflation, different parts of space-time grew at different rates. This could have carved off different sections — different universes — with potentially different laws of physics.

Related: Best multiverse movies and TV shows: from Dr Strange to Dr Who

"It's hard to build models of inflation that don't lead to a multiverse," Alan Guth, a theoretical physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said during a news conference in March 2014 concerning the gravitational waves discovery. (Guth is not affiliated with that study.)

"It's not impossible, so I think there's still certainly research that needs to be done. But most models of inflation do lead to a multiverse, and evidence for inflation will be pushing us in the direction of taking [the idea of a] multiverse seriously."

While we can understand how the universe we see came to be, it's possible that the Big Bang was not the first inflationary period the universe experienced. Some scientists believe we live in a cosmos that goes through regular cycles of inflation and deflation, and that we just happen to be living in one of these phases.

JWST and the Big Bang

A telescope is almost like a time machine, allowing us to peer back into the distant past. With the aid of the Hubble space telescope, NASA has shown us galaxies as they were many billions of years ago — and Hubble's successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, has the ability to look even deeper into the past.

NASA hopes it will see all the way back to when the first galaxies formed, nearly 13.6 billion years ago. And unlike Hubble, which sees mainly in the visible waveband, JWST is an infrared telescope — a big advantage when looking at very distant galaxies. The expansion of the universe means that waves emitted from them are stretched out, so light that was emitted at visible wavelengths actually reaches us in the infrared.

The Big Bang Theory: becoming a household name

The name "Big Bang Theory" has been a popular way to talk about the concept among astrophysicists for decades, but it hit the mainstream in 2007 when a comedy T.V. show with the same name premiered on CBS.

Running for 279 episodes over 12 seasons, the show "The Big Bang Theory" followed the lives of a group of scientists, which included physicists, astrophysicists and aerospace engineers. The show explores the group's nerdy friendships, romances and squabbles. Its first season premiered on Sept. 24, 2007, and the show officially ended on May 16, 2019.

Although the show itself didn't dive too much into actual science, the showrunners did hire UCLA astrophysicist David Saltzberg as a science consultant for the entire run of the show, according to Science magazine. Science consultants are often hired for sci-fi and science-related shows and movies to help keep certain aspects realistic.

Thanks to Saltzberg, the characters' vocabulary included a host of science jargon and the whiteboards in the background of labs, offices and apartments throughout the show were filled with a variety of equations and information.

Over the course of the show, Saltzberg said, those whiteboards became coveted space as researchers sent him new work that they hoped might be featured there. In one episode, Saltzberg recalled, new evidence of gravitational waves was scrawled across a whiteboard that ostensibly belonged to famed physicist Steven Hawking, who also approved the text.

The show took some liberties, as it was fictional. This included fabricating some new scientific concepts and fictionalizing the politics of Nobel prizes and academia, according to Fermilab physicist Don Lincoln.

Related: How 'The Big Bang Theory' sent Howard Wolowitz to space

Notably, several characters in the series take trips. One episode sees main characters Leonard, Sheldon, Raj and Howard set out on a research expedition to the Arctic — many physics experiments are best performed at or near the extreme environments of the poles. Another put aerospace engineer Howard on a Russian Soyuz spacecraft and, later, a model of the International Space Station along with real-life astronaut Mike Massimino.

Additional resources

Discover more about CMB on NASA's webpage on putting the Big Bang theory to the test. NASA has also put together what the Big Bang might have looked it in this animation. Here are 5 quick facts about the Big Bang from How It Works magazine.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace