25 weird and wild solar system facts

There are so many interesting solar system facts, here are some of our favorites.

- 1. The solar system is really big

- 2. Our neighborhood is huge

- 3. Uranus spins sideways

- 4. Jupiter's moon is volcanic chaos

- 5. The biggest volcano

- 6. The biggest canyon

- 7. Winds on Venus blow scientists away

- 8. Water is everywhere

- 9. We've sent spacecraft to every planet

- 10. We could contaminate other planets with our microbes

- 11. Mercury is shrinking

- 12. Pluto's unexpected mountains

- 13. Pluto's bizarre atmosphere

- 14. Rings aren't just for Saturn

- 15. The Great Red Spot is shrinking

- 16. Solar telescope spots sungrazer comets

- 17. Planet Nine?

- 18. Neptune is too hot

- 19. Van Allen Belts are weird

- 20. Miranda is all torn up

- 21. Saturn's two-tone moon

- 22. Titan's liquid cycle

- 23. Organics are everywhere

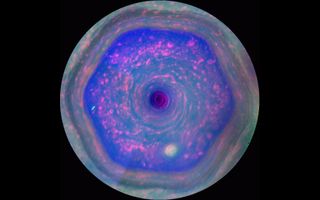

- 24. Saturn's hexagonal storm

- 25. Why is the sun's atmosphere so hot?

With so many interesting solar system facts, we've narrowed them down to 25 of our favorites.

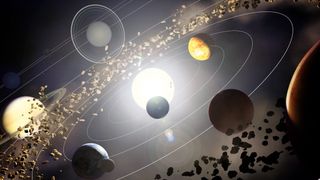

Our solar system consists of the sun and everything that orbits that sun, like the eight (once nine) planets we all know from elementary school. But the main planets, as diverse and fascinating as they are, are just the beginning. Earth's neighbors in space include comets, asteroids, dwarf planets, mysterious moons and a host of strange phenomena that are so out-of-this-world they elude explanation.

Scientists have discovered ice-spewing volcanoes on Pluto, while Mars is home to a truly "grand" canyon the size of the United States. There may even be a giant, undiscovered planet lurking somewhere beyond Neptune. Read on for some of the strangest facts about the solar system.

1. The solar system is really, really big

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft was launched in 1977. More than three decades later, in 2012, it became the first human-made object to enter interstellar space by crossing the heliopause, or the edge of the heliosphere. That's the boundary beyond which most of the sun's ejected particles and magnetic fields dissipate.

But, according to NASA, "if we define our solar system as the Sun and everything that primarily orbits the Sun, Voyager 1 will remain within the confines of the solar system until it emerges from the Oort cloud in another 14,000 to 28,000 years."

Related: Voyager 2's trip to interstellar space deepens some mysteries beyond our solar system

2. Even just our neighborhood is really, really big

Depending on how carefully you do the calculations and how you arrange them, all of the planets in the solar system could fit in between Earth and its moon. The distance between the Earth and the moon varies, as does the diameter of each of the planets — they're wider at their equators, so Saturn or Jupiter or both would have to be tilted sideways for this to work, according to news site Slate. But imagine lining them all up, pole to pole. They'd just barely squeeze in between us and our closest companion in space, blocking out the sky with their rings and gas giant bulk as they did so. (Of course, in all practicality we'd have other problems to worry about, too. Our little moon creates vast tides on Earth already — the gravitational perturbation from our new proximity to Jupiter alone would keep any of us from admiring the view.)

The moon is the farthest from Earth that we've ever sent humans, and it's both mind-bogglingly distant and incredibly close depending on how you think about it. Eight enormous planets could fit between here and there, and yet according to NOAA, the distance from Earth to the sun is more than 390 times the distance from the Earth to the moon.

Scientists use an approximation of the Earth-to-sun distance, also known as one astronomical unit or AU, to compare distances within the solar system. Jupiter is about 5.2 AU from the sun, and Neptune is 30.07 AU from the sun or approximately 30 times as far from the star as Earth

3. Uranus spins sideways

Uranus usually appears in classroom solar system models as a featureless blue ball, but this gas giant of the outer solar system is pretty weird on closer inspection. First, the planet rotates on its side, appearing to roll around the sun like a ball, according to NASA's Uranus guide. The most likely explanation for the planet's unusual orientation (about 90 degrees sideways compared to the other planets) is that it underwent some sort of titanic collision in the ancient past.

Uranus' tilt causes what NASA considers to be the most extreme seasons in the solar system. For about a quarter of each Uranus year (or 21 Earth years, as each Uranus year is 84 years long), the sun shines directly over the north or south pole of the planet. That means for more than two decades on Earth, half of Uranus never sees the sun at all.

Scientists monitor these extreme seasons on Uranus and expected that the 2007 equinox on the planet might cause unusual weather. But it was seven years later that the atmosphere erupted into wild unpredicted storms, making Uranus more of a puzzle than ever.

4. Jupiter's moon Io has towering volcanic eruptions

Compared to Earth's peaceful moon, Jupiter's moon Io may come as a surprise. The Jovian moon has hundreds of volcanoes and is considered the most active moon in the solar system, sending plumes of sulfur up to 190 miles (300 kilometers) into its atmosphere. According to a statement from NASA, Io's volcanos emit one ton (more than 900 kilograms) of gases and particles into the space near Jupiter each second.

Io's eruptive nature is caused by the immense forces the moon is exposed to, nestled in Jupiter's gravitational well and its magnetic field. The moon's insides tense up and relax as it orbits closer to, and farther from, the planet, generating enough energy for volcanic activity.

Scientists are still trying to figure out how heat spreads through Io's interior, though, making it difficult to predict where the volcanoes exist using scientific models alone.

5. Mars boasts a volcano bigger than the entire state of Hawaii

While Mars seems quiet now, gigantic volcanoes once dominated the surface of the planet. This includes Olympus Mons, the biggest volcano ever discovered in the solar system. At 374 miles (602 km) across, the volcano is comparable to the size of Arizona. It's 16 miles (25 kilometers) high, or triple the height of Mount Everest, the tallest mountain on Earth. By volume, according to NASA, Olympus Mons is 100 times larger than Earth's largest volcano, Hawaii's Mauna Loa.

Scientists speculate that volcanoes on Mars can grow to such immense size because gravity there is much weaker than it is on Earth.

In addition, while Earth's crust constantly moves, the Martian crust likely does not (although the debate among researchers continues). The Hawaiian islands were formed as a hot spot in the mantle created a chain of volcanoes in the crust cruising by above it, so if the surface of Mars isn't moving, a volcano could build-up for longer in one spot.

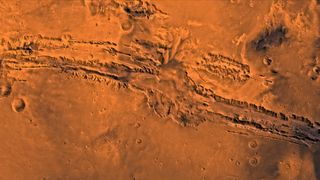

6. Mars' largest valley could eat the Grand Canyon for breakfast

At 2,500 miles (4,000 km) long, the immense system of Martian canyons known as Valles Marineris is more than 10 times as long as the Grand Canyon on Earth. Valles Marineris escaped the notice of early Mars spacecraft (which flew over other parts of the planet) and was finally spotted by the global mapping mission Mariner 9 in 1971. And what a sight it was to miss — Valles Marineris could stretch from coast to coast of the entire United States!

The lack of active plate tectonics on Mars makes it tough to figure out how the canyon formed. Some scientists think that a chain of volcanoes on the other side of the planet, known as the Tharsis Ridge (which includes Olympus Mons), somehow bent the crust from the opposite side of Mars. That cataclysmic force activated cracks in the crust, vast amounts of sub-surface water that emerged to carve away rock, and glaciers that crunched new pathways into the canyon system.

7. Venus is swept by super-powerful winds… that some hope could harbor life

Venus is a hellish planet with a high-temperature, high-pressure environment on its surface. Bone-dry and hot enough to melt lead, it's not exactly a welcoming environment (and has probably always been inhospitable to life). When heavily shielded Venera spacecraft from the Soviet Union landed there in the 1970s, according to NASA each lasted a few minutes or, at most, a few hours before melting or being crushed beyond their ability to function.

But even above its surface, the planet has a bizarre environment. Scientists have found that its upper winds flow 50 times faster than the planet's rotation. The European Venus Express spacecraft (which orbited the planet between 2006 and 2014) tracked the winds over long periods and detected periodic variations. It also found that the hurricane-force winds appeared to be getting stronger over time.

A 2020 study that thrilled some astrobiologists detected phosphine, a possible sign of decaying biological matter, high in the Venusian clouds. Could they be a sign of life? Not without sufficient water, claim follow-up studies that firmly reject the possibility of life in Venus' dry windy atmosphere.

8. There is water everywhere

Water was once considered a rare substance in space. In fact, water ice exists all over the solar system: It's a common component of comets and asteroids, for starters.

Water can be found as ice in permanently shadowed craters on Mercury and the moon, although we don't know if there's enough to support prospective human colonies in those places. Mars also has ice at its poles, in frost and likely below the surface dust. Even smaller bodies in the solar system have ice: Saturn's moon Enceladus, and the dwarf planet Ceres, among others.

NASA scientists suspect Jupiter's moon Europa may be the most likely known candidate for extraterrestrial life because, against all expectations, there is likely liquid water below its cracked and frozen surface. Europa, much smaller than Earth, may host a deep ocean that researchers suggest could contain twice as much water as all of Earth's oceans combined.

But we know that not all ice is the same. A close-up examination of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko by the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft, for example, revealed a different kind of water ice than the kind found on Earth.

9. Spacecraft have visited every planet

We've been exploring space for more than 60 years, and have been lucky enough to get close-up pictures of dozens of celestial objects. Most notably, we've sent spacecraft to all of the planets in our solar system — Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — as well as two dwarf planets, Pluto and Ceres.

The bulk of the flybys came from NASA's Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which left Earth more than four decades ago and are still transmitting data from interstellar space. Between them, the Voyagers clocked visits to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, thanks to an opportune alignment of the outer planets.

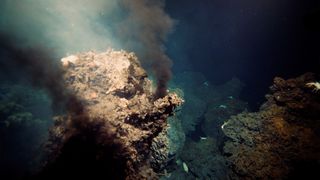

10. Spacecraft could bring contaminants to inhabitable (or inhabited) locations in the solar system

So far, scientists have found no evidence that life exists elsewhere in the solar system. But as we learn more about how "extreme" microbes live in underwater volcanic vents or frozen environments, more possibilities open up for where they could live on other planets.

Microbial life is now considered likely enough on Mars that scientists take special precautions to sterilize spacecraft headed to the planet. NASA chose to crash its Galileo spacecraft into Jupiter rather than risk it contaminating the potentially habitable oceans of Europa.

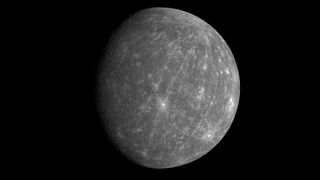

11. Mercury is still shrinking

Mercury is already the smallest planet in the solar system (excluding the dwarf planet Pluto, of course), and the second-densest after Earth. And it's only getting smaller and denser.

For many years, scientists believed that Earth was the only tectonically active planet in the solar system. That changed after the Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft did the first orbital mission at Mercury, mapping the entire planet in high definition and getting a look at the features on its surface.

In 2016, data from MESSENGER revealed cliff-like landforms known as fault scarps. Because the fault scarps are relatively small, scientists are sure that they weren't created that long ago and that the planet is still contracting 4.5 billion years after the solar system was formed.

12. There are mountains on Pluto

Pluto is a tiny world at the edge of the solar system, so scientists assumed the dwarf planet would have a fairly uniform, crater-pocked environment. That changed when NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew by in 2015, sending back pictures that altered our view of Pluto forever.

Related: Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons mission in pictures

Among the astounding discoveries were icy mountains that are 11,000 feet (3,300 meters) high, indicating that Pluto must have been geologically active as little as 100 million years ago. But geological activity requires energy, and the source of that energy inside Pluto is a mystery. The sun is too far away from Pluto to generate enough heat for geological activity, and there are no large planets nearby that could have caused such disruption with gravity.

13. Pluto has a bizarre atmosphere

Pluto's observed atmosphere broke all the predictions. Scientists saw the unexpected haze extending as high as 1,000 miles (1,600 km), rising higher above the surface than the atmosphere on Earth. As data from NASA's New Horizons mission flowed in, scientists analyzed the haze and discovered some surprises there, too.

Scientists found about 20 layers in Pluto's atmosphere that are both cooler and more compact than expected. This affects calculations for how quickly Pluto loses its nitrogen-rich atmosphere to space. NASA's New Horizons team found that tons of nitrogen gas escape the dwarf planet by the hour, but somehow Pluto can constantly resupply that lost nitrogen. The dwarf planet is likely creating more of it through geological activity.

14. Rings are much more common than we thought

We've known about Saturn's rings since telescopes were invented in the 1600s, but it took spacecraft and more powerful telescopes built in the last 50 years to reveal more. We now know that every planet in the outer solar system — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — has a ring system. But the rings differ from planet to planet: Saturn's spectacular halo, made in part of sparkly, reflective water ice, is not repeated anywhere else. Instead, the rings of the other giants are likely made of rocky particles and dust.

Rings aren't limited to planets, either. In 2014, for example, astronomers discovered rings were around the asteroid Chariklo.

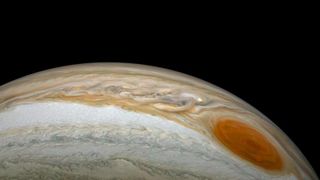

15. Jupiter's Great Red Spot is shrinking

Along with being the solar system's largest planet, Jupiter also hosts the solar system's largest storm. Known as the Great Red Spot, it's been observed in telescopes since the 1600s and studied from modern instruments like NASA's Juno, which recently provided evidence that the storm is hundreds of miles tall (and likely fed by winds from thousands of miles below, too). The storm has been a raging conundrum for centuries, but in recent decades another mystery emerged: the spot is getting smaller.

In 2014, the storm was only 10,250 miles (16,500 km) across, about half of its historic size. The shrinkage is being monitored in professional telescopes and also by amateurs. Amateurs are often able to make more consistent measurements of Jupiter because viewing time on larger, professional telescopes is limited and often split between different objects.

Related: Best telescopes 2022: Top picks for viewing planets, galaxies, stars and more

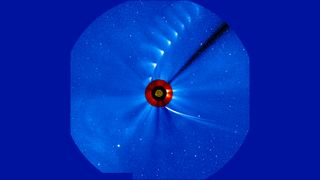

16. Most comets are spotted with a sun-gazing telescope

Comets used to be the province of amateur astronomers, who spent night after night scouring the skies with telescopes. While some professional observatories also made discoveries while viewing comets, that began to change with the launch of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) in 1995.

Since then, the spacecraft has found more than 2,400 comets, which is a pretty productive side-mission for a telescope meant to observe just the sun. These comets are nicknamed "sungrazers." Many amateurs still participate in the search for comets by picking them out from raw SOHO images. One of SOHO's most famous observations came when it watched the breakup of the bright Comet ISON in 2013.

17. There may be a huge planet at the edge of the solar system

In January 2015, California Institute of Technology astronomers Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown announced — based on mathematical calculations and simulations — that there could be a giant planet lurking far beyond Neptune. Several teams are now on the search for this theoretical "Planet Nine," and research suggests it could be located within the decade.

This large object, if it exists, could help explain the movements of some objects in the Kuiper Belt, an icy collection of objects beyond Neptune's orbit. Brown has already discovered several large objects in that area that in some cases rivaled or exceeded the size of Pluto. (His discoveries were one of the catalysts for changing Pluto's status from planet to dwarf planet in 2006.)

But scientists are pursuing another theory, too: that "Planet Nine" could in fact be a grapefruit-sized black hole, warping space similarly to the way a gigantic planet would. And yet another team suggests that the weird movements of the far-flung Kuiper Belt occupants could be the collective influence of several small objects, not an undiscovered planet or black hole at all.

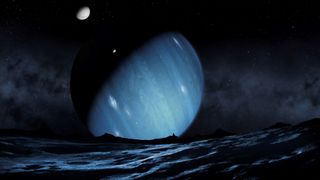

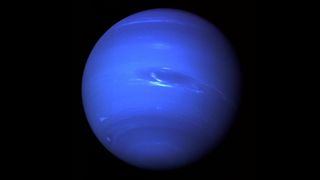

18. Neptune is too hot

Neptune is roughly 30 times as far from the sun as Earth, and it gets correspondingly less heat and light. But it radiates far more heat than it's taking in and has far more activity in its atmosphere than planetary scientists would suspect, especially compared to nearby Uranus. Uranus is closer to the sun and yet radiates about the same amount of heat as Neptune, and scientists aren't sure why.

Winds on Neptune can blow up to 1,500 miles per hour (2,400 km/h). Is all that energy coming from the sun, from the planet's core, or gravitational contraction? Researchers are working to find out.

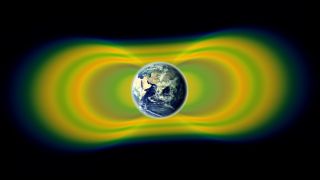

19. Earth's Van Allen belts are more bizarre than expected

Earth has several bands of magnetically trapped, highly energetic charged particles surrounding our planet, known as the Van Allen belts (named after the discoverer of the phenomenon.) While we've known about the belts since the dawn of the space age, the Van Allen Probes (launched in 2012) have provided our best-ever view of them. They've uncovered quite a few surprises along the way.

We now know that the belts expand and contract according to solar activity. Sometimes the belts are very distinct from one another, and sometimes they swell into one massive unit. An extra radiation belt (beyond the known two) was spotted in 2013. Understanding these belts helps scientists make better predictions about space weather or solar storms.

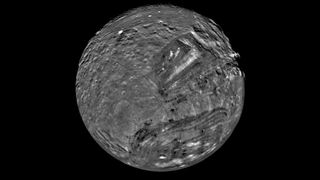

20. What happened to Miranda?

One of the most bizarre moons in the outer solar system is Miranda, a shadowy moon of Uranus observed only once when Voyager 2 got a glimpse in 1986. Miranda hosts sharp ridges, craters and other major disruptions on its surface that would usually be the result of volcanic action. Tectonic activity could cause that kind of surface, but Miranda is much too small to generate that kind of heat on its own.

Researchers think that gravitational pull from Uranus could have generated the push-pull action needed to heat, churn and contort Miranda's surface. But to know for sure, we'll need to send another spacecraft to check out the moon's unobserved northern hemisphere.

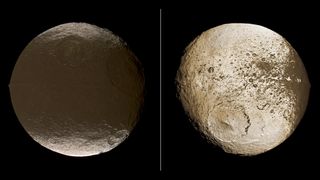

21. Saturn's yin-yang moon

Saturn's moon Iapetus has a very dark hemisphere that always faces away from the planet and a very light hemisphere that always faces toward Saturn. Most asteroids, moons and planets are relatively uniform across their surfaces, but Iapetus sometimes shines brightly enough to be spotted by Giovanni Cassini's telescope in the 1600s, and then dims down by several magnitudes when oriented in the other direction.

Current research suggests that Iapetus, also known as Saturn VIII, is made mostly of water ice. As the moon's darker side faces the sun, scientists hypothesize, water ice sublimated away from that area, leaving darker rock behind. That could have created a positive feedback loop, as dark material heats up more than bright, reflective ice: as the darker, warmer side of the moon lost its ice, it became easier to heat up each time it faced the sun, hastening the loss of more ice.

22. Titan has a liquid cycle, but it's definitely not water

Another weird moon in Saturn's system is Titan, which hosts a liquid "cycle" that moves material between the atmosphere and the surface. That sounds a lot like Earth's water cycle, but Titan's immense lakes are filled with methane and ethane, possibly over a layer of water.

Researchers hope to use data from the international Cassini mission to tease out some of Titan's secrets before designing a submarine that might one day plumb the depths of the mysterious moon.

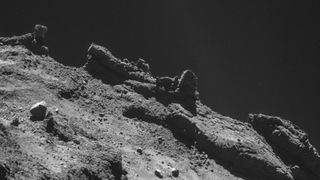

23. Organics molecules are everywhere

Organics are complex carbon-based molecules found in living things, but which can be created by non-biological processes too. While organic molecules are common on Earth, they can unexpectedly be found in many other places in the solar system too. Scientists have found organics on the surface of Comet 67P, for example. The discovery bolstered the case that organic molecules to jump-start life on Earth could have been brought to the surface from space.

Organics have also been found on the surface of Mercury, on Saturn's moon Titan (which gives Titan its orange color) and on Mars

24. Saturn has a hexagonal-shaped storm

Saturn's northern hemisphere has a raging six-sided storm nicknamed "the hexagon." This hexagon, a towering multilayered storm, has been there for decades, if not hundreds of years.

The strange storm was discovered in the 1980s but was barely visible until the Cassini mission flew by between 2004 and 2017. Images and data from Cassini reveal the storm to be 180 miles (300 km) tall, 20,000 miles (32,000 km) wide and composed of air moving at about 200 mph (320 km/h).

25. The solar atmosphere is much hotter than the sun's surface

While the sun's visible surface — the photosphere — is 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 degrees Celsius), its upper atmosphere has temperatures in the millions of degrees. It's a large temperature differential with little explanation.

Related: How hot is the sun?

NASA has several sun-gazing spacecraft on the case, however, and they have some ideas for how the heat is generated. One is "heat bombs," which happen when magnetic fields cross and realign in the corona. Another is when plasma waves move from the sun's surface into the corona.

With new data from the Parker Solar Probe (which recently became the first human-made object to touch the sun) coming in all the time, we're closer than ever to unlocking the mysteries at the heart of our solar system.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace

- Daisy DobrijevicReference Editor