May full moon 2023: The Flower Moon gets eclipsed

The full moon of May, also called the Flower Moon, will occur the afternoon of May 5.

This year's Flower Moon will be accompanied by a lunar eclipse.

The full moon of May, also called the Flower Moon, will occur the afternoon of May 5, at 1:34 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time (1734 UTC), according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. Observers in Continental Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and the western Pacific Islands will see a penumbral lunar eclipse, in which the moon dims slightly but does not get completely dark.

The full moon occurs when the moon is exactly on the opposite side of the Earth from the sun, and the lunar phase is determined by the position of the moon itself in its orbit rather than the view from wherever one happens to be on Earth. This means the timing of the lunar phases depends on one's time zone, so from locations such as Cape Town, South Africa, Warsaw or Cairo the full moon occurs at 7:34 p.m. local time, while in Tokyo or Seoul it is at 3:34 a.m. on May 6.

Related: Full moon calendar 2023: When to see the next full moon

Looking for a telescope to see the moon? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

When we look at the moon we are seeing the sunlight reflected to Earth; the only time this changes is during eclipses. A lunar eclipse happens when the moon enters the Earth's shadow, as on the night of May 5-6 at 1514 UTC (11:14 a.m. EDT). Unlike solar eclipses, which are only visible along a narrow path, lunar eclipses can be seen anywhere the moon is above the horizon. This time the Western Hemisphere, British Isles and most of Scandinavia will be on the day side of the Earth, and the moon will not have risen yet.

Unlike a more typical partial or total lunar eclipse, in a penumbral eclipse the moon passes through the outer part of the Earth's shadow, called the penumbra. The inner part, where the Earth blocks all of the light from the sun to the moon, is called the umbra. Most of the time the moon either passes through the Earth's darker umbral shadow, creating a partial or total lunar eclipse, or only part of the moon passes through the penumbra.

In the latter case, the darkening of the moon is difficult to see; the penumbral shadow only "tints" the moon slightly and if the whole moon isn't covered by the penumbra that slight dimming is overwhelmed by the brightness of the lunar surface. This eclipse will have a much rarer condition, in which the entire moon will pass into the penumbra, but not the umbra. This means the slight darkening is more noticeable. If you were standing on the moon you would see the Earth block part of the sun's light, but not all of it – you'd have a partial solar eclipse.

How high in the sky the moon is when the eclipse starts depends on one's location. To see the full effect of the penumbral eclipse properly one must be far east enough that the moon hasn't exited the penumbral shadow by moonrise. For example, in Paris, the moon rises at 9:16 p.m. local time on May 5 and the eclipse is almost over; the slight darkening at the top edge of the moon won't be readily visible. In Rome, the moon rises at 8:13 p.m. local time, nearly an hour after maximum eclipse. However, the moon is still largely covered in the penumbral shadow; the eclipse ends at 9:31 p.m. for Romans. In Istanbul the eclipse starts at 6:22 p.m. local time, with the moon rising at 8:01 p.m. and maximum eclipse occurring at 8:22 p.m. The eclipse ends at 10:31 p.m., so Turkish observers will be able to see the full effects of the penumbra's darkening of the surface.

As one gets further east the moon rises as the eclipse begins; one of the places where that happens is Tehran, where the moon rises at 6:45 p.m. local time – the eclipse starts only a minute before that. Observers will see the rising moon touch the penumbra (which will be on the lower left) and see it get slightly darker over the course of about two hours. Maximum eclipse is at 8:52 p.m. and the eclipse ends at 11:01 p.m. In New Delhi, one will see the eclipse start well after moonrise, which is at 6:45 p.m. local time. The eclipse starts at 8:44 p.m., with maximum eclipse at 10:52 p.m.

Much further east the moon is in the western sky as the eclipse starts. In Tokyo the eclipse starts just after midnight on May 6 at 12:14 a.m. local time and ends at 4:31 a.m.; the Moon sets at 4:48 a.m.

For those who won't see the eclipse, there is an ordinary full moon, in the constellation Libra. New York City observers will see moonrise at about on 8:13 p.m. local time on May 5, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. In Miami, the moon rises at 8:08 a.m. Eastern Time. In Buenos Aires, the moon rises at 6:05 p.m. local time. Moonrise times will differ by latitude because the Earth is tilted on its axis; the Southern Hemisphere nights are longer, so the sun sets earlier and the moon rises earlier (from the point of view of people at that latitude).

One full moon phenomenon is that they are on the exact opposite side of the sky as the sun; the position of the moon is the position the sun will be in six months later (or six months earlier). In the Northern Hemisphere the full moon tends to be lower in the sky in the late spring and summer months, while in the Southern Hemisphere, where it is winter, the moon is higher. The result is that full moon nights in the wintertime in mid-northern latitudes tend to be brightly lit; add to that the odds that there is snow on the ground, and you get a night that is easier for people to see by.

Full moons in December and January are also high enough that they can appear smaller – this is an illusion created by the fact that there is nothing near the horizon to give the moon scale. During the Northern Hemisphere summer, the moon, being lower in the sky, doesn't appear to light the night up as much, though being lower it appears larger because it's closer to the horizon, and we see objects near it to show its size (for similar reasons at sunset the sun can appear to be larger than it is, but if one were to actually measure its angular size in the sky there would be little difference from any other time of day).

Full moons are so bright that through binoculars or a small telescope the glare can even require a moon filter. Unlike observing the sun, (which one should never do without specialized equipment) there is no danger to one's eyes, but details can be harder to see than when the moon is a crescent or during quarter phases ("half" moons). The problem is shadows – or lack thereof. A full moon means we are seeing the surface at lunar noontime (an astronaut standing on the moon would see the sun directly overhead). At noon there are no shadows towards the center of the lunar disk, and few of them even towards the edges. Moon filters can make some features stand out by altering the colors we see (for example some are greenish, which highlights some shades of gray). If one waits a few days after the full moon or observes a few days before, shadows make spotting the surface features easier.

You can prepare for the next full moon or eclipse with our guide on how to photograph a lunar eclipse, as well as how to photograph the moon with a camera in general, can help you make the most of the event. If you need imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography to make sure you're ready for the next eclipse.

If you're looking for binoculars or a telescope to observe the moon, check out our guides for the best binoculars and best telescopes.

Related: The ultimate guide to observing the moon

Visible planets

On the night of the full moon Venus is at its highest in the evening sky; on May 8 the planet will be at an altitude of 37 degrees as the sun sets at 7:59 p.m. in New York, according to In-the-sky.org. The date that Venus is highest at sunset changes with one's latitude; this is because the angle the planet's path in the sky makes against the horizon changes (it tends to get steeper as one nears the tropics). So for example in Miami, the planet reaches its highest elevation on May 11; sunset is at 7:57 p.m. local time. In Quito the planet reaches its highest elevation a full month later (though the difference is small) – on June 11, when the sun sets at 6:16 p.m. local time, the planet it at 43 degrees. Venus isn't as high for Southern Hemisphere viewers; In Buenos Aires, on the night of the full moon, the sun sets at 6:07 p.m. and Venus is some 21 degrees high in the northwest; it reaches maximum elevation of 32 degrees at sunset in July. Venus is so bright that it is usually the first "star" visible in the evening, so it's a relatively easy observing target.

Mars is above Venus and to the east (the left) for Northern Hemisphere skywatchers; the planet will be relatively high in the sky and by about 8:30 p.m. easily visible, in the constellation Gemini. On May 6 the planet sets at 1:06 a.m. in New York; the local timing is similar for cities at the same latitude.

Jupiter rises just ahead of the sun, at 5:03 a.m. local time in New York, but since the sun rises at 5:25 a.m. it will be difficult to spot as the sky starts getting lighter about then; the planet won't be easily visible away from the solar glare for another month.

Saturn is easier to see; the ringed planet rises at 3:06 a.m. local time and is in the constellation Aquarius. For observers at about 40 degrees north (New York City, Chicago and Sacramento) the planet gets to about 15 degrees above the southeastern horizon by 4:30 a.m. Saturn is brighter than the stars of Aquarius, so even from a city location it should be prominent and obvious.

Meteor showers

Full moons tend to be hard on meteor watchers, and this one is no exception; the full moon occurs right around the peak time for the Eta Aquarid meteor shower. This one is better placed for people in further south; Aquarius never gets that high from the Northern Hemisphere, but closer to the equator the constellation is higher and easier to see. Even so, this particular shower doesn't produce the numbers of meteors that the more famous Perseid shower does, and with a bright moon seeing any meteors will be harder; count yourself lucky if you spot any at all.

A good strategy is to look away from where the moon is, and about 30 to 90 degrees from the radiant of the shower. That means looking towards the constellations Aquila and Cygnus in the southeast during the wee hours of the morning, if one is in the Northern Hemisphere. For antipodeans, it's easier, since even though the moon will be higher in the sky, one can look due south towards Achernar, the end of Eridanus the River, where the relatively faint constellations such as Tucana (the Toucan) will allow meteors to stand out.

Constellations

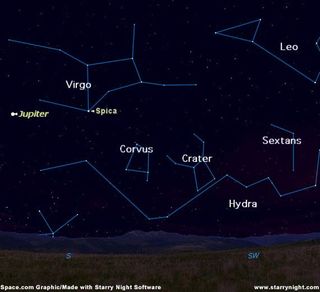

In May the spring stars are high in the evening and the summer stars take over after midnight. At around sunset Leo the Lion is almost directly overhead; one can use Big Dipper to find Leo by tracing the "pointers" in the front of the Dipper's bowl south, away from Polaris, the Pole Star.

To the east of Leo is Virgo, which can also be found using the Dipper. One can "arc to Arcturus" by making a sweeping motion along the handle and hitting Arcturus, the brightest star in Bootes, the Herdsman. If one continues that arc, the next bright star is Spica, Virgo's "alpha" star Below Leo and Virgo is a line of fainter stars that is the Hydra and a grouping called Crater the Cup; both are fainter and harder to see from city locations. That said, to find the Hydra, one can start by looking for a star below Spica that is about half as bright; that's the end of the Hydra's tail.

To the right of that will be a quadrangle of fainter stars marking the Crow (Corvus) which sits right above the next section of the Hydra's body. Looking further right another group of four stars is the base of the Cup, which makes a trapezoid. Just to the right of that is the next star in the Hydra, and one can see a faint "W" shape ending in a brighter star called Alphard, or Alpha Hydrae. The Hydra's head is a small ring of faint stars to the right of Alphard and between Procyon and Regulus.

For Southern Hemisphere sky watchers in the mid-latitudes, by 9 p.m. Scorpio will be rising in the southeast. (it will be to the right, or east of the Moon), and Alpha Centauri, otherwise known as Rigil Kentaurus, will be higher towards the south. The Southern Cross will be higher still, at about the 10 o'clock position if one looks due south. The cross in fact points to the south celestial pole, though there is no corresponding star like Polaris there.

High in the southwest, one can see the three constellations that make up the legendary Argo: Carina, the Ship's Keel, Puppis, the Poop Deck, and Vela, the Sail. Canopus, the brightest star in Carina, is about 35 degrees high in the southwest, and one can find it by looking for Sirius, the Dog Star, which is the brightest star in the sky. Canopus will be a similarly bright star to the left of Sirius.

The full moon of May is often called a flower moon, and the term comes from the blooms that appear in North America around that time. Some peoples, such as the Ojibwe, called it something similar, according to the Ontario Native Literacy Coalition – the moon was called Waawaaskone Giizis, the Flower Moon. The Cree called it the Frog Moon, as May is when frogs tend to become active. Both Anishinaabe and Cree traditions reflect the environment in northeastern North America, where the two peoples live. Other nations had different traditions; the Cherokee call the May lunation a planting moon, and that is reflected in their word for the month of May.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the Māori described the lunar month of Pipiri, which occurs from May to June: "all things on earth are contracted because of the cold," according to the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Editor's Note: If you snap an image of the full Flower Moon and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.