Pluto: Everything you need to know about the dwarf planet

Pluto was once considered the ninth planet in the solar system. It was demoted in 2006.

Pluto is the largest known dwarf planet in the solar system and used to be considered the ninth and most distant planet from the sun.

The strange world is located in the Kuiper Belt, a zone beyond the orbit of Neptune brimming with hundreds of thousands of rocky, icy bodies each larger than 62 miles (100 kilometers) across as well as 1 trillion or more comets.

Pluto stopped being a planet in 2006 when it was reclassified as a dwarf planet, a demotion that attracted controversy and stirred debate in the scientific community and among the general public.

Related: Why isn't Pluto a planet anymore?

American astronomer Percival Lowell first suggested that Pluto existed in 1905 when he observed strange deviations in the orbits of Neptune and Uranus. Lowell thought there must be another whose gravity is tugging on these ice giants, causing discrepancies in their orbits. Lowell proceeded to predict the mystery planet's location in 1915 but died 15 years before its discovery. Pluto was eventually discovered in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh at the Lowell Observatory, based on predictions by Lowell and other astronomers.

Pluto got its name from 11-year-old Venetia Burney of Oxford, England, who suggested to her grandfather that the new world get its name from the Roman god of the underworld. Her grandfather then passed the name on to Lowell Observatory. The name also honors Percival Lowell, whose initials are the first two letters of Pluto.

Pluto FAQs answered by an expert

We asked Emily Safron, an astronomy instructor at Case Western Reserve University, who received her Ph.D. in physics from Louisiana State University under Dr. Tabetha Boyajian, a few frequently asked questions about Pluto.

Emily Safron is an astronomy instructor at Case Western Reserve University.

Why is Pluto no longer considered a planet?

For a long time, we thought Pluto was unique in the Kuiper Belt. But as astronomers discovered more and more about the Kuiper Belt (and the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter), we learned that there are lots of objects like Pluto. More like Pluto, in some ways, than Pluto is like the other planets. Finding all these new objects, it became necessary for astronomers to get more specific about what we mean by the word "planet," and figure out which category Pluto fit into.

The three rules astronomers of the International Astronomical Union came up with to define a planet are: The object must orbit the sun; the object must be massive enough to be roughly spherical; and the object must have cleared its orbit of any objects of comparable mass to its own (that is, it must be gravitationally dominant in its orbit). Pluto satisfies the first two of these criteria, but not the third. Even one of its own moons, Charon, is about half of Pluto's size. So, rather than being the runt of the planet group, Pluto is now the "king" of the dwarf planet group!

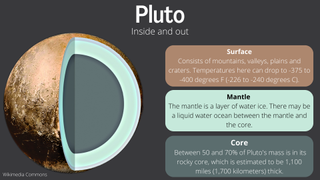

What is Pluto made of?

Astronomers believe that Pluto probably has a rocky core. Outside of that, but still deep in the interior, there's likely an ocean of water, covered by another layer of frozen water ice. The surface crust is a layer of various ices, mostly nitrogen ice, with giant mountains of water ice, and traces of methane and carbon monoxide ices.

Does Pluto have an atmosphere?

Yes. Much like its crust, Pluto's atmosphere is composed of nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide. There are also haze particles in Pluto's atmosphere, which scatter blue light. These particles start out high in Pluto's atmosphere as ionized methane and nitrogen. As the ions interact with each other, they combine into more complex molecules, and start to collect an outer shell of volatile ices. As the haze particles get more massive, they start to fall through the atmosphere, collecting more ice. This "snow" falls to Pluto's surface a reddish gray.

What does Pluto look like?

Since Pluto is so far from Earth, little was known about the dwarf planet's size or surface conditions until 2015, when NASA's New Horizons space probe made a close flyby of Pluto. New Horizons showed that Pluto has a diameter of 1,473 miles (2,370 km), less than one-fifth the diameter of Earth, and only about two-thirds as wide as Earth's moon.

Observations of Pluto's surface by the New Horizons spacecraft revealed a variety of surface features, including mountains that reach as high as 11,000 feet (3,500 meters), comparable to the Rocky Mountains on Earth. While methane and nitrogen ice cover much of the surface of Pluto, these materials are not strong enough to support such enormous peaks, so scientists suspect that the mountains are formed on a bedrock of water ice.

Pluto's surface is also covered in an abundance of methane ice, but New Horizons scientists have observed significant differences in the way the ice reflects light across the dwarf planet's surface. The dwarf planet also possesses ice ridge terrain that appears to look like a snakeskin; astronomers spotted similar features to Earth's penitentes, or erosion-formed features on mountainous terrain. The Pluto features are much larger; they are estimated at 1,650 feet (500 m) tall, while the Earth features are only a few meters in size.

Another distinct feature on Pluto's surface is a large heart-shaped region known unofficially as Tombaugh Regio (after Clyde Tombaugh; regio is Latin for region). The left side of the region (an area that takes on the shape of an ice cream cone) is covered in carbon monoxide ice. Other variations in the composition of surface materials have been identified within the "heart" of Pluto.

In the center-left of Tombaugh Regio is a very smooth region unofficially known by the New Horizons team as "Sputnik Planum," after Earth's first artificial satellite, Sputnik. This region of Pluto's surface lacks craters caused by meteorite impacts, suggesting that the area is, on a geologic timescale, very young — no more than 100 million years old. It's possible that this region is still being shaped and changed by geologic processes.

These icy plains also display dark streaks that are a few miles long and aligned in the same direction. It's possible the lines are created by harsh winds blowing across the dwarf planet's surface.

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has also revealed evidence that Pluto's crust could contain complex organic molecules.

Related: Photos of Pluto and its moons

Pluto's surface is one of the coldest places in the solar system. Temperatures here can drop to around minus 375 to minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 226 to minus 240 degrees Celsius). When compared with past images, pictures of Pluto taken by the Hubble Space Telescope revealed that the dwarf planet had apparently grown redder over time, apparently due to seasonal changes.

Pluto may have (or may have had) a subsurface ocean, although the evidence is still out on that finding. If the subsurface ocean existed, it could have greatly affected Pluto's history. For example, scientists found that the zone of Sputnik Planitia redirected Pluto's orientation due to the amount of ice in the area, which was so heavy it affected Pluto overall; New Horizons estimated the ice is roughly 6 miles (10 km thick). A subsurface ocean is the best explanation for the evidence, the researchers added, although looking at less likely scenarios, a thicker ice layer or movements in the rock may be responsible for the movement. If Pluto did have a liquid ocean, and enough energy, some scientists think Pluto could harbor life.

What is Pluto made of?

Some of Pluto's parameters, according to NASA:

Atmospheric composition: Methane, nitrogen. Observations by New Horizons show that Pluto's atmosphere extends as far as 1,000 miles (1,600 km) above the surface of the dwarf planet.

Magnetic field: It remains unknown whether Pluto has a magnetic field, but the dwarf planet's small size and slow rotation suggest it has little to no such field.

Chemical composition: Pluto probably consists of a mixture of 70 percent rock and 30 percent water ice.

Internal structure: The dwarf planet probably has a rocky core surrounded by a mantle of water ice, with more exotic ices such as methane, carbon monoxide and nitrogen ice coating the surface.

Pluto's orbital characteristics

Pluto's highly elliptical orbit can take it more than 49 times as far out from the sun as Earth. Since the dwarf planet's orbit is so eccentric, or far from circular, Pluto's distance from the sun can vary considerably. The dwarf planet actually gets closer to the sun than Neptune is for 20 years out of Pluto's 248-Earth-years-long orbit, providing astronomers a rare chance to study this small, cold, distant world.

Pluto's rotation is retrograde compared to the solar systems' other worlds; it spins backward, from east to west.

Average distance from the sun: 3,670,050,000 miles (5,906,380,000 km) — 39.482 times that of Earth

Perihelion (closest approach to the sun): 2,755,773,000 miles (4,434,987,000 km) — 30.151 times that of Earth

Aphelion (farthest distance from the sun): 4,538,698,000 miles (7,304,326,000 km) — 48.023 times that of Earth

As a result of that orbit, after 20 years as the eighth planet (in order going out from the sun), in 1999, Pluto crossed Neptune's orbit to become the farthest planet from the sun (until it was demoted to the status of dwarf planet).

When Pluto is closer to the sun, its surface ices thaw and temporarily form a thin atmosphere, consisting mostly of nitrogen, with some methane. Pluto's low gravity, which is a little more than one-twentieth that of Earth's, causes this atmosphere to extend much higher in altitude than Earth's. When traveling farther away from the sun, most of Pluto's atmosphere is thought to freeze and all but disappear. Still, in the time that it does have an atmosphere, Pluto can apparently experience strong winds. The atmosphere also has brightness variations that could be explained by gravity waves, or air flowing over mountains.

While Pluto's atmosphere is too thin to allow liquids to flow today, they may have streamed along the surface in the ancient past. New Horizons imaged a frozen lake in Tombaugh Regio that appeared to have ancient channels nearby. At some point in the ancient past, the planet could have had an atmosphere roughly 40 times thicker than on Mars.

In 2016, scientists announced that they might have spotted clouds in Pluto's atmosphere using New Horizons data. Investigators saw seven bright features that are near the terminator (the boundary between daylight and darkness), which is commonly where clouds form. The features are all low in altitude and roughly about the same size, indicating that these are separate features. The composition of these clouds, if they are indeed clouds, would likely be acetylene, ethane and hydrogen cyanide.

Does Pluto have any moons?

Pluto has five moons: Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberos and Hydra, with Charon being the closest to Pluto and Hydra the most distant.

In 1978, astronomers discovered that Pluto had a very large moon nearly half the dwarf planet's own size. This moon was dubbed Charon, after the mythological demon who ferried souls to the underworld in Greek mythology.

Because Charon and Pluto are so similar in size, their orbit is unlike that of most planets and their moons. Both Pluto and Charon orbit a point in space that lies between them, similar to the orbits of binary star systems, For this reason, scientists refer to Pluto and Charon as a double dwarf planet, double planet or binary system.

Pluto and Charon are just 12,200 miles (19,640 km) apart, less than the distance by flight between London and Sydney. Charon's orbit around Pluto takes 6.4 Earth-days, and one Pluto rotation — a Pluto-day — also takes 6.4 Earth-days. This is because Charon hovers over the same spot on Pluto's surface, and the same side of Charon always faces Pluto, a phenomenon known as tidal locking.

While Pluto has a reddish tint, Charon appears more grayish. In its early days, the moon may have contained a subsurface ocean, though the satellite probably can't support one today. Compared with most of the solar system's planets and moons, the Pluto-Charon system is tipped on its side in relation to the sun.

Observations of Charon by New Horizons have revealed the presence of canyons on the moon's surface. The deepest of those canyons plunges downward for 6 miles (9.7 km). A long swatch of cliffs and troughs stretches for 600 miles (970 km) across the middle of the satellite. A section of the moon's surface near one pole is covered in a much darker material than the rest of the planet. Similar to regions of Pluto, much of Charon's surface is free of craters — suggesting the surface is quite young and geologically active. Scientists saw evidence of landslides on its surface, the first time such features have been spotted in the Kuiper Belt. The moon may have also possessed its own version of plate tectonics, which cause geologic change on Earth.

In 2005, scientists photographed Pluto with the Hubble Space Telescope in preparation for the New Horizons mission and discovered two other tiny moons of Pluto, now dubbed Nix and Hydra. These satellites are two and three times farther away from Pluto than Charon. Based on measurements by New Horizons, Nix is estimated to be 26 miles (42 km) long and 20 miles (32 km) wide, while Hydra is estimated at 34 miles (55 km) long and 70 miles (113 km) wide. It is likely that Hydra's surface is coated primarily in water ice.

Scientists using Hubble discovered a fourth moon, Kerberos, in 2011. This moon has a doubled-lobed shape and the larger lobe is around 5 miles (8 km) across and the smaller lobe is around 3 miles (5 km) across. On July 11, 2012, a fifth moon, Styx, was discovered (with an estimated width of 6 miles or 10 km), further fueling the debate about Pluto's status as a planet.

The leading hypothesis for the formation of Pluto and Charon is that a nascent Pluto was struck with a glancing blow by another Pluto-size object. Most of the combined matter became Pluto, while the rest spun off to become Charon, this idea suggests. The other four moons may have formed from the same collision that created Charon.

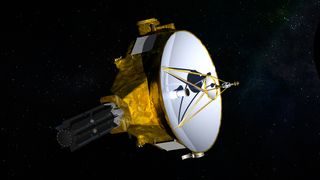

Missions to Pluto

NASA's New Horizons mission is the first probe to study Pluto, its moons and other worlds within the Kuiper Belt up close. It was launched on January 2006, and successfully made its closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015.

The New Horizons probe carries some of the ashes of Pluto's discoverer, Clyde Tombaugh.

The limited knowledge of the Pluto system created unprecedented dangers for the New Horizons probe. Prior to the mission's launch, scientists knew of the existence of only three moons around Pluto. The discovery of Kerberos and Styx during the spacecraft's journey fueled the idea that more satellites could orbit the dwarf planet, unseen from Earth. Collisions with unseen moons, or even small bits of debris, could have seriously damaged the spacecraft. But the New Horizons design team equipped the space probe with tools to protect it during its journey.

In October 2021, New Horizons made history when it returned the first close-up images of Pluto and it's moons.

Additional resources

Explore Pluto in more detail with NASA's 10 cool things we learned about Pluto article. Read more about Pluto and the developing landscape of our Solar System with the International Astronomical Union. Discover the six things dwarf planets have taught us about the solar system with the American Geophysical Union's science news magazine Eos.

Bibliography

International Astronomical Union. IAU. Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://www.iau.org/public/themes/pluto/

NASA. (2021, August 5). Pluto. NASA. Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/dwarf-planets/pluto/overview/

Talbert, T. (Ed.). (2020, July 14). 10 cool things we learned about pluto. NASA. Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://www.nasa.gov/feature/five-years-after-new-horizons-historic-flyby-here-are-10-cool-things-we-learned-about-plut-0

Wendel, J. A. (2016, August 17). Six things dwarf planets have taught us about the solar system. Eos. Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://eos.org/articles/six-things-dwarf-planets-have-taught-us-about-the-solar-system

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scott is a staff writer for How It Works magazine and has previously written for other science and knowledge outlets, including BBC Wildlife magazine, World of Animals magazine, Space.com and All About History magazine. Scott has a masters in science and environmental journalism and a bachelor's degree in conservation biology degree from the University of Lincoln in the U.K. During his academic and professional career, Scott has participated in several animal conservation projects, including English bird surveys, wolf monitoring in Germany and leopard tracking in South Africa.

- Daisy DobrijevicReference Editor